197019711972 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concert 1970 |

|||

MAY 1970 |

|||

05 may |

Londres, Angleterre |

Royal Albert Hall |

|

JULY 1970 |

|||

07 july |

New York, USA / |

Carnegie Hall |

|

AUGUST 1970 |

|||

06 aug |

New York, USA |

Shea Stadiumticket for the Festival For Peace featuring Poco, Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Paul Simon, John Sebastian, Miles Davis, Johnny Winter, Richie Havens, and The James Gang at Shea Stadium, New York, NY. |

|

Concert 1971 |

|||

JANUARY 1971 |

|||

?? jan |

New York, USA |

Shea Stadium |

|

JULY 1971 |

|||

?? july |

New York City |

Shea Stadium |

|

1972Tracks List Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard/ |

|||

FEBRUARY 1972APRIL 1972 |

|||

28 apr |

Cleveland, Ohio |

|

|

MAY 1972 |

|||

08 may |

Cleveland, OH, USA |

|

|

JUNE 1972 |

|||

14 june |

New York |

MSG New YorkTogether for McGovern |

|

July 1972

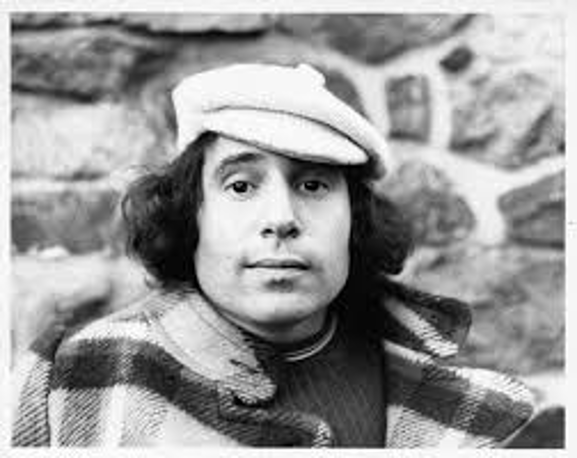

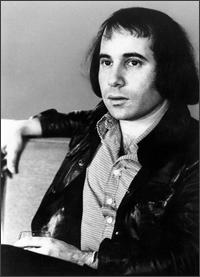

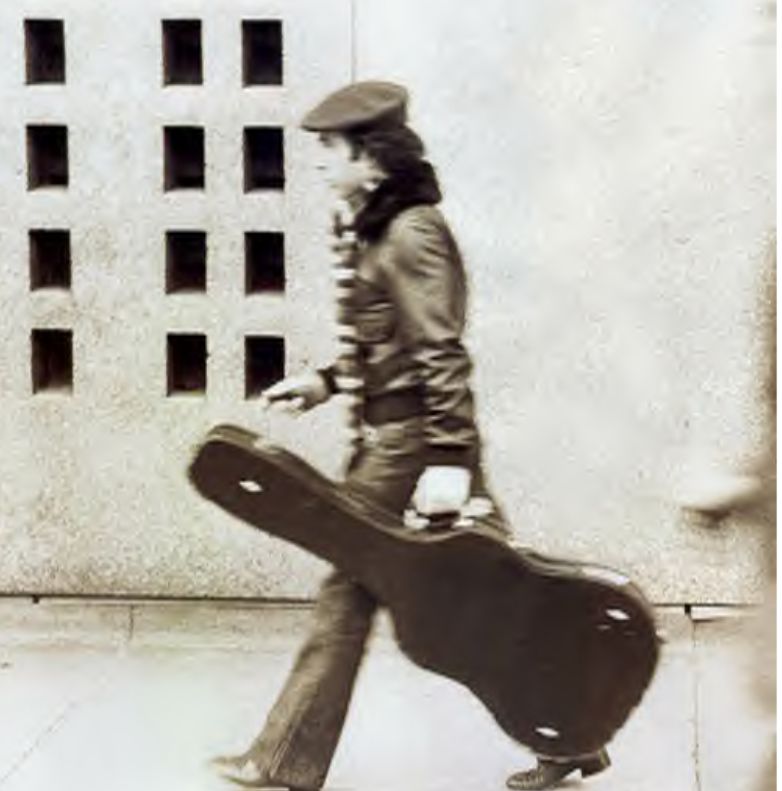

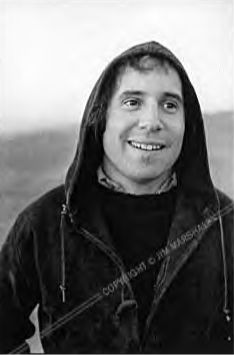

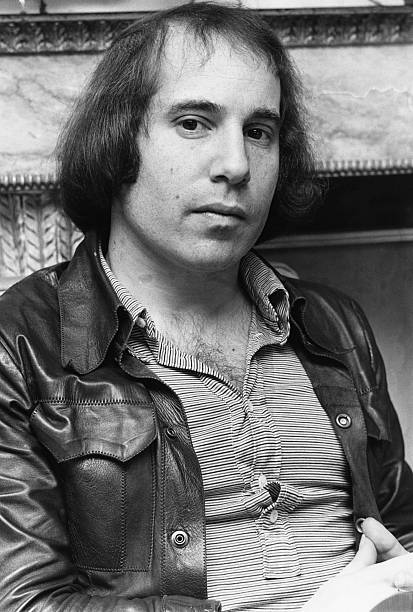

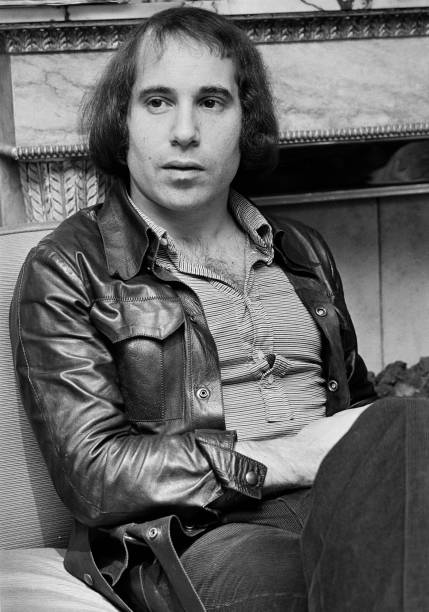

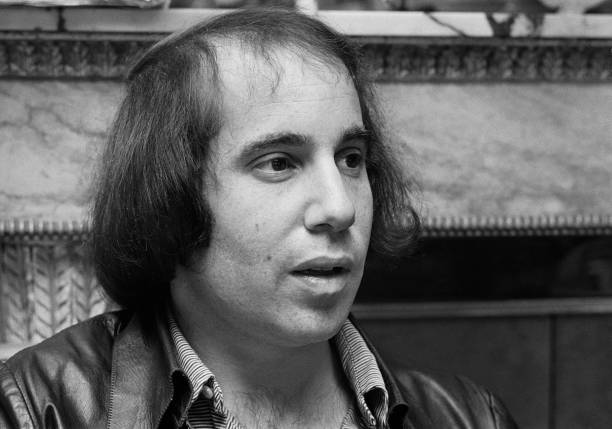

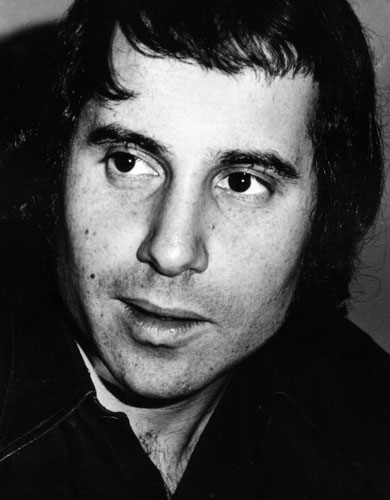

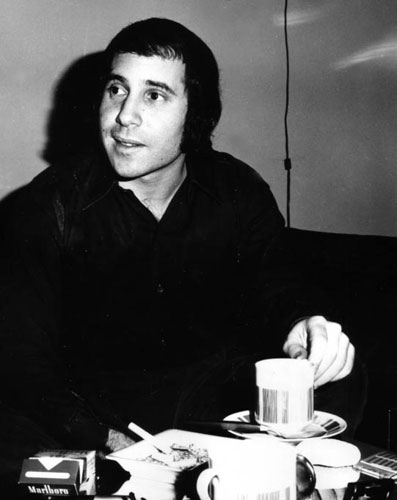

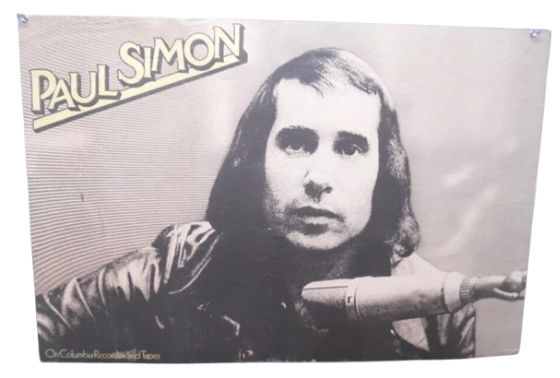

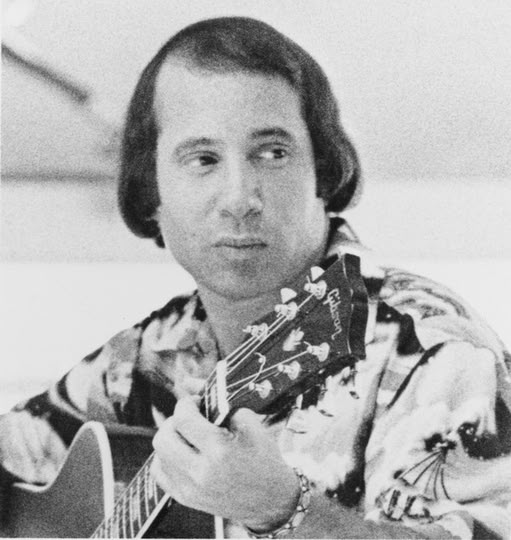

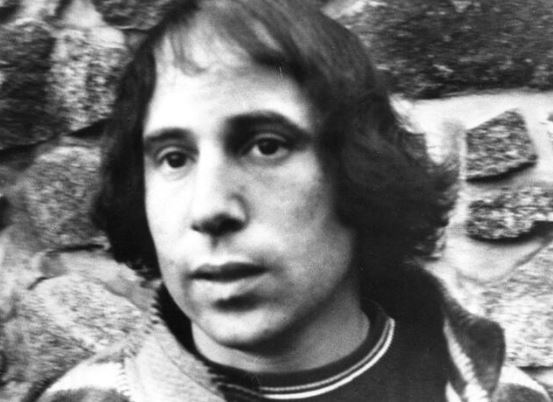

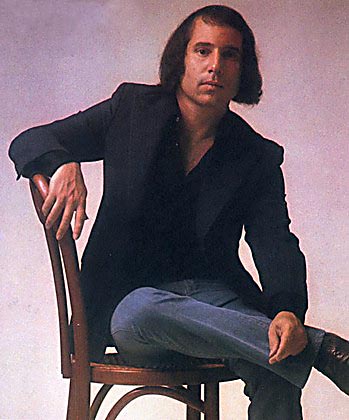

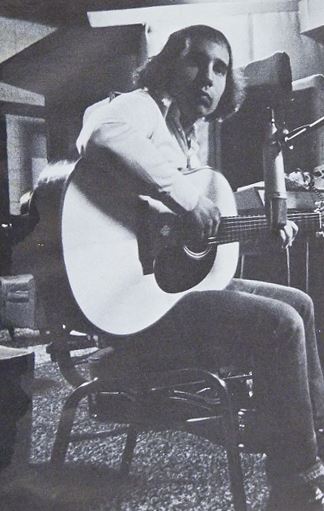

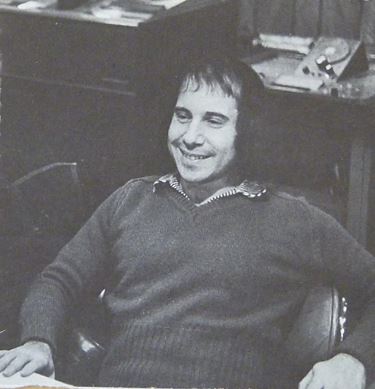

The interviewer (J.L.) met Paul Simon over three days in late May and early June, recording roughly 13 hours of conversation at Simon’s Upper East Side New York home (where Simon lives part-time, alongside a farm in Pennsylvania). Simon’s wife Peggy appears briefly; they are expecting their first child in September. At the time, Simon had just finished producing an album for Los Incas (the group whose track underpinned “El Condor Pasa”) and was planning to produce his second solo album in September–October, followed by a U.S. tour in November. J.L. describes Simon as open but extremely deliberate—answering with the same perfectionist care he brings to writing and recording. A major focus is Simon’s relationship with Art Garfunkel and how Simon & Garfunkel ended. Simon calls the relationship “cautious,” governed by rules to avoid mutual irritations. He emphasizes there was no single dramatic meeting that “ended” the duo; rather, the breakup became inevitable during the difficult, exhausting making of Bridge Over Troubled Water, when working together stopped being enjoyable and personal frictions mounted. After the album, Garfunkel pursued acting (Carnal Knowledge) while Simon made a solo album; they never formally declared it over, but it became clear over time that it was. Simon explains that the duo’s massive success had become a burden: the expectation to follow Bridge Over Troubled Water would have created intense pressure and likely disappointment. Ending the partnership freed him to write and sing in directions that would not naturally fit Simon & Garfunkel (he cites “Mother and Child Reunion”). He also describes an underlying creative imbalance: Garfunkel was primarily a singer, while Simon wrote the songs, shaped tracks, chose musicians, and increasingly led studio decisions—especially because Garfunkel was sometimes absent during Bridge. Simon portrays the group as effectively a three-way partnership (Simon, Garfunkel, and engineer/co-producer Roy Halee), where “equal voices” sometimes meant Simon set aside his own judgment. Making his first solo record taught him that every detail ultimately had to be his decision (tempo, takes, feel). The interview includes specific behind-the-scenes accounts. Simon says Garfunkel initially did not want to sing “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” believing Simon should do it; Simon admits to occasional resentment when audiences cheered “his” song. He also recalls disputes over what would be the twelfth track on Bridge (including an abandoned song, “Cuba Si, Nixon No”), with exhaustion from a TV special, touring, and sponsor conflicts contributing to the album being released with 11 songs. Simon calls Bridge their best album and contrasts aesthetics: he preferred preserving the right feel even if technically imperfect, whereas Garfunkel and Halee leaned toward a sweeter, bigger, more “lush” polish. He offers a detailed step-by-step description of how “Bridge” was recorded—key changes, days spent refining the gospel piano part, adding a third verse later, layering instruments, and revising string arrangements. Simon also discusses his eclectic musical interests and approach to cross-genre collaboration. He criticizes American musical provincialism, explains how “El Condor Pasa” grew from a Los Incas recording he loved, and recounts how “Mother and Child Reunion” took shape in Jamaica by letting local musicians play in their own idiom and adapting to them. He shares that the song’s title came from a Chinese-menu dish (“chicken and eggs”) and that the lyrics were shaped by grief after a beloved dog was killed, which triggered fears about losing Peggy. Other sections cover his writing style (mixing humor and seriousness, and pairing pretty music with darker lyrics), studio techniques (loops, subtle sound effects), Simon & Garfunkel’s vocal layering and increasing studio perfectionism (including punching-in), and his view that songs—not recordings—tend to survive longest culturally. Simon speaks candidly about drugs: he describes marijuana/hash use and a few acid experiences as ultimately negative (withdrawal, paranoia, depression, impaired writing) and says he quit entirely when he began psychoanalysis; he later quit cigarettes as well, noting improvements in singing. He expresses support for feminism, influenced by Peggy, and reflects on how rigid gender roles harm relationships—especially with a child on the way. Finally, he addresses fame, groupies (he found casual hookups embarrassing and often avoided post-show contact), and politics. He recalls disappointment with a poorly organized 1968 benefit concert and later expresses respect for George McGovern’s integrity while remaining wary of political idealization. He rejects the idea that musicians have special political obligations simply because they are musicians; he believes the primary obligation is to become excellent at the craft, with activism remaining a personal choice. He is also sharply critical of certain political pop slogans (including some of John Lennon’s work), which he sees as cliché or manipulative.

|

|||